Haitian Colour

Nashville made me feel properly grateful for the freedom to travel, maybe for the first time. The day before I left, four of my Haitian colleagues were refused US visas for a work training trip. I booked US flights on a whim and jumped on a plane. And I complain about restricted movement here.

I stayed in a motel that I would have turned my nose up at a year ago. I thought, ‘A bed and a shower with hot water coming out of it? That’s good enough for me’.

I was peppering to get to a shopping centre and then I was physically unable to shop like I used to. I looked at the overstocked shelves and rails and thought, ‘All tat. Obscene levels of tat. Tat that will end up in a rubbish mountain somewhere like Haiti. I bought St. Patrick’s Day tat with half a heart for old times’ sake. Haiti colours EVERYTHING now.

Germany’s Just Better

I got my hair cut at the Opry Mills Shopping Mall and had this conversation with the hairdresser:

Me: Do you like living in Nashville?

Her: No. Well, you asked … (shrug).

Me: What’s wrong with Nashville?

Her: I lived in Germany for eight years. Nashville’s not Germany.

Me: What’s so great about Germany?

Her: Oh, you know. The buses. The trains … (faraway look).

I first I felt baffled. Then I rejoiced. Because one service worker in America, one renegade redhead, has escaped the forced implantation of the US Chirpy Chip TM. She was probably in Germany when they came for her. They’re probably still looking now.

Cowboy Couture

Big boots, baby boots and boot accessories. Wrangler work-wear for daytime and buckskin tassels at night. The fashion in Nashville will take you from the rodeo to the honky-tonk. If that’s a journey you wish to make.

Water Shows the Hidden Heart

An Egyptian taxi driver called Ibrahim told me that he loves Enya and blasted her greatest hits at me in the car. I felt floored by homesickness, what with the rain outside and the Enya inside. Ibrahim asked me what language Enya was singing in on track number nine. I listened carefully and said, ‘It’s probably Irish. I’m sure it’s Irish. Or is it Latin? Or fecking … Maori?’ I googled it and discovered it’s a language called Loxian. Made up by Enya. Ibrahim processed this and said, ‘That lady, she’s a genius’. I thought, ‘Scarlet for you Enya. What a load of auld shite’.

The Fear

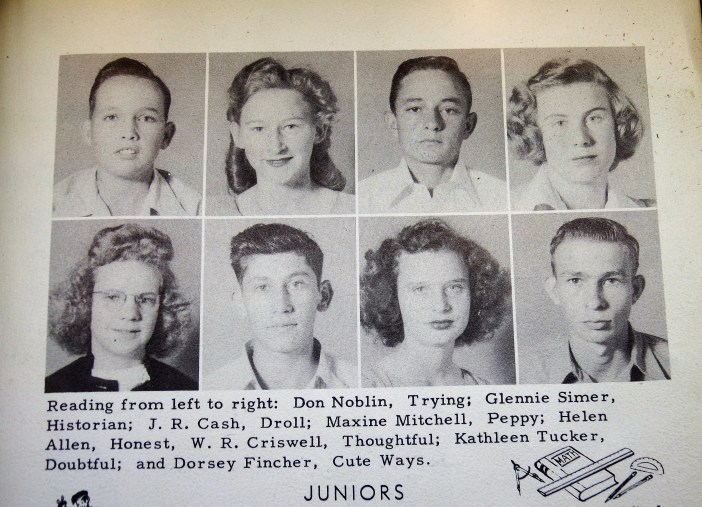

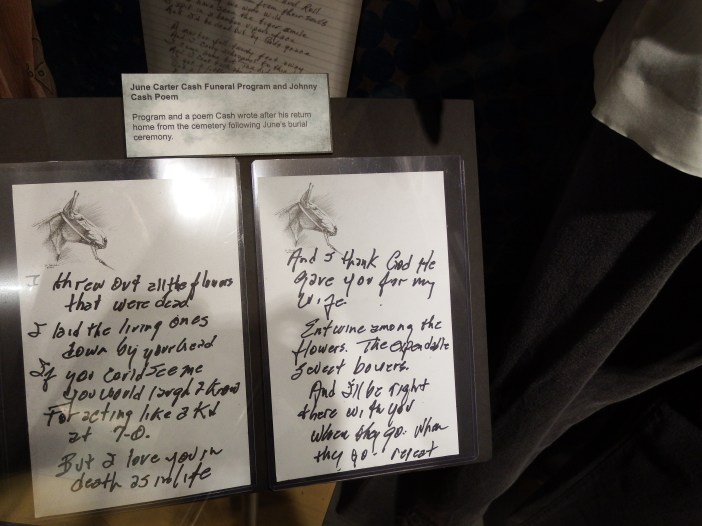

I watched the ‘Hurt’ video at the Johnny Cash museum and cried on account of how his hand shook in it. How could I not, standing there among the relics of a legendary life? The milky marbles he played with as a boy, the ‘Future Farmers of America’ membership card that he didn’t need for long, the stage outfits and size 13 boots looming out of low-lit cabinets, the absolutely KILLING note that he wrote to his wife June when he came home from her funeral. Johnny Cash was a mountain of a man in every sense of the word but old age, illness and death come to us all. When existential fear hits, I do what it takes to outrun it. Novelty photo shoot then? Any wonder? None at all.

Always, Yes and No

Feeling lonely everywhere I went because people kept asking, ‘Are you waiting for someone? Just you this evening? Do you need another menu?’ One lady tried to sell me Dead Sea Salt beauty products by asking skin-unrelated questions such as, ‘Are you married? Do you have children? All alone then …’ She needs to go straight back to sales school. I saw a sign in the airport that helped. God always moves to soothe me.

I don’t know about you …

Watching two young lads from Athy take Music City by storm. Feeling sick thinking, ‘That’s it now. They’re on their way to stardom and there’s no turning back’. They say fame arrests your emotional development. If that’s true, then Picture This will be feeling 22 forever. I hope to Jesus they have some life skills; I hope they can drive and pay their own bills.

Connecting the dots like you wouldn’t believe.

When I was home at Christmas, I had wobbles about going back to Haiti. I had a conversation with God about it. I said, ‘If you want me to go back, give me one good reason to’. The next song on the radio was ‘Use Somebody’ by the Kings of Leon. I heard the lyrics ‘You know that I could use somebody. Someone like you and all you know and how you speak’. I felt comforted because all I want is to be useful; that more than anything.

I met the producer of the new Picture This album at their gig in Nashville. I said, ‘What’s your name again? Jacquir? That’s a very UNUSUAL name, if you don’t mind me saying’. I had the chats with him about the lads’ astonishing talent and said, ‘Yes, but will you make sure that they sound like THEMSELVES on the record though?’ Jacquir assured me that he would.

I drifted back to my budget accommodation and googled the producer’s credentials. I found out that he’s Jacquir King, who has won three Grammy awards and been nominated for over thirty. I felt mortified that I told a Grammy winner how to do his job. Then I noticed that one of his Grammys was for his work on ‘Use Somebody’ by the Kings of Leon. I never met a Grammy winner before. I probably never will again. Meeting that particular one felt like God doffing his hat at me. It felt like a God nod and a wink. I said you wouldn’t believe me. That doesn’t make it less true.

It All Begins with a Song

I visited the Grand Ole Opry and felt sad that my parents might never get to. We grew up on American country music. I still know every word of country anthems like ‘Joshua’ by Dolly Parton and ‘Crystal Chandeliers’ by Charley Pride. I can’t advocate the ‘Joshua’ approach to hillbilly romance (orphan girl meets social outcast) but I can say this; if Irish people had listened to Charley Pride, the Celtic Tiger might never have happened. That song is a cautionary tale that I’ll never forget – ‘Will the timely crowd that has you laughing loud help you dry your tears? When the new wears off of your crystal chandeliers’. What we do when the new wears off defines us.

I stood centre stage at the Grand Ole Opry and wondered if any of the country legends who had performed there knew the colour they added to the lives of people like my parents, bringing up five bold babies in the homogenous, hermetically sealed, hangdog Ireland of the Seventies. Maybe not. I did my first novelty photo shoot of the trip for my Mammy and Daddy, who gave us an appreciation for songs that tell a story and leave you reeling when they end, thinking, ‘Jesus help us! What happened then?’